Six goals in four games. A hat-trick in the semi-final. Two more in the final as Brazil claimed the trophy they so desperately craved.

Arriving in Sweden for the World Cup as an unknown, Pelé left as a star who would go on to achieve sporting immortality. But one man within the Brazil camp had argued against him playing.

Professor João Carvalhaes was the team’s psychologist. In stark contrast to his modern-day counterparts, whose remit tends to be strictly focused on supporting players’ performance and mental health, he had real influence over selection.

Pelé’s results in the psychometric tests Carvalhaes applied was the reason for his somewhat dubious advice, which was ignored in this instance. The legendary footballer himself later said of Carvalhaes’ methods: “They were either ahead of their time for football or just odd, or maybe both.”

But beyond doubt is his place in history as a sporting pioneer. Carvalhaes introduced psychology laboratories to South American football almost 30 years before the concept was adopted in Europe.

Back in 1950s Brazil, they wanted all the help they could get.

Brazil’s 1950 and 1954 World Cup campaigns had been torturous. In 1950 defeat in the final by Uruguay at the Maracanã, the spiritual home of Brazilian football, prompted mourning across the country.

The 1954 tournament, held in Switzerland, ended in ignominy as Brazil were reduced to nine men during an ugly 4-2 quarter-final loss to Hungary in a match nicknamed ‘The Battle of Berne’.

While the national team attempted to move on from the emotional trauma, a little-known psychologist was making his entrance into Brazilian domestic football.

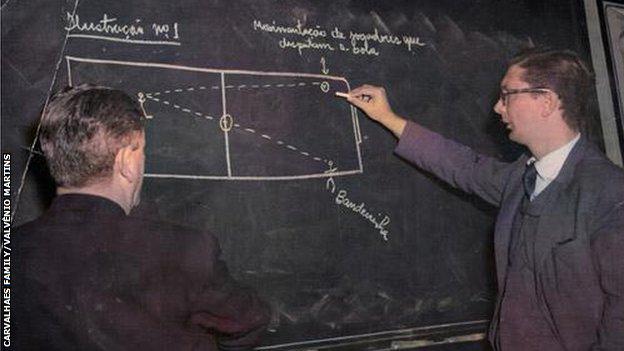

Carvalhaes joined São Paulo in 1957, leaving a job training referees for the city’s football federation. The club’s interest was piqued by the psychology laboratory he had founded, the likes of which would not be seen in Europe until AC Milan’s ‘Mind Room’ of the late 1980s.

The lab was built at the federation’s headquarters and housed 10 tests examining cognitive functions such as stereoscopic vision (depth perception). Carvalhaes used the tests to help highlight the skills trainee referees needed to hone before qualifying to officiate professional matches.

Carvalhaes set thresholds for each variable he monitored, with candidates scoring below a particular benchmark considered unable to referee. For example, participants who recorded a result slower than 50 hundredths of a second during the ‘reaction time test’ fell into this category.

He combined his day job with regular evening stints as a boxing commentator and journalist, during which he adopted the pseudonym João do Ringue (Joao of the Ring). In contrast to his ringside persona, though, Carvalhaes’ touchline demeanour was reflective, according to former colleague Dr José Glauco Bardella.

“Arriving at the training ground, you could see everyone excited, but João would be in the corner, quiet, hands in his pockets, just observing,” he told a 2000 documentary on Carvalhaes’ work, made by the São Paulo Regional Council of Psychology.

Carvalhaes may have been watchful, but he was far from a mere spectator.

After São Paulo won the Campeonato Paulista in 1957, the team’s first state championship since 1953, Carvalhaes was heralded for his role in a selection decision that proved key to victory.

Club director Manoel Raimundo Paes de Almeida said the replacement of regular midfielder Ademar with fellow playmaker Sarara, who then shone in a crunch match with Corinthians, was based on Carvalhaes’ concerns about Ademar’s state of mind.

A year later the Brazilian Football Confederation (CBF) came calling. Vice-president Paulo Machado de Carvalho, the man charged with planning for the forthcoming World Cup, asked Carvalhaes to join the team’s technical committee. It was an offer too good to turn down.

Credit: BBC

Comments are closed.