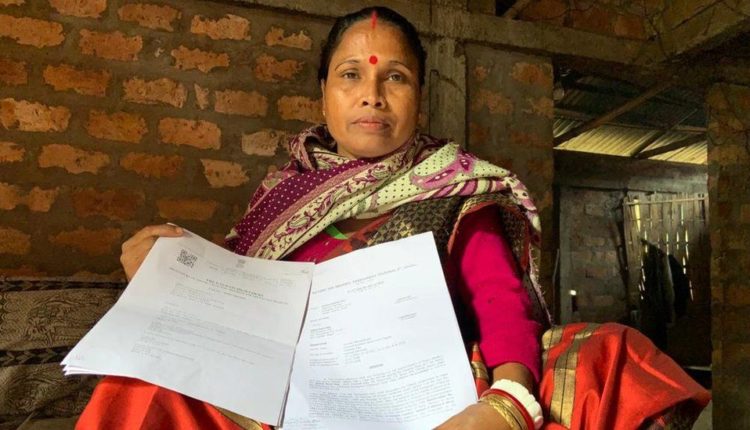

A seven-year-long fight by a woman in India’s north-eastern state of Assam to regain her citizenship has left her with debt and fear. BBC Hindi’s Dilip Kumar Sharma reports.

Sefali Rani Das, 42, was used to feeling scared when she saw the police.

For years, they visited her home – in Cachar district, which borders Bangladesh – to serve notices that asked her to provide proof that she was an Indian citizen.

She won’t need to hide anymore – in January, after years of attending court hearings, she received an order that declared she was a legal resident of India.

But the price was high – the family is now struggling to pay back the money they borrowed to fight the case. They also have to pursue another case to prove that her husband is an Indian citizen too.

“What my family and my children have gone through in the past few years, I don’t think there can be bigger hardships than that,” Ms Das says.

Ms Das is among hundreds of thousands of people in Assam who have been declared illegal migrants over the past few decades – they are asked to prove their citizenship, which involves an arduous process that could end in detention or even deportation if unsuccessful.

It is a burning issue in Assam. In 1951, the state began recording details of its residents in the National Register of Citizens (NRC) – its purpose was to determine who was born in the state and was Indian, and who might be a migrant from East Pakistan, as neighbouring Bangladesh, a Muslim-majority country, was known then.

“I was born here and I studied here. Then how did I become a Bangladeshi all of a sudden? This question kept haunting me,” Ms Das said.

Under a 1985 agreement between the federal government and leaders of a movement against illegal immigrants in Assam, anyone who could prove they entered the state before 1 January 1966 would be granted citizenship.

Those who entered between 1 January 1966 and 24 March 1971 – the day before Bangladesh declared independence from Pakistan – would have to register themselves with the government. And those who entered the state after 24 March 1971 can be declared foreigners and deported.

Since the late 1980s, special courts called Foreigners Tribunals have been hearing cases of alleged illegal migrants, usually reported by the border police.

The issue gained international attention in 2019, when the NRC was updated, leaving 1.9 million people stateless and at the mercy of the tribunals. The tribunals function as a quasi-judicial system in the state and are often accused of bias and inconsistencies in their rulings.

Source: BBC

Comments are closed.