Letter from Africa: I Was Tortured in The Gambia

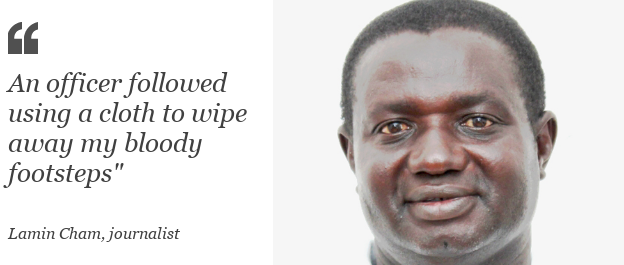

In our series of letters from African journalists, Lamin Cham, editor of The Gambia’s Standard newspaper and a former BBC reporter, explains why he wants to testify at the new truth and reconciliation commission.

Our former President Yahya Jammeh went into exile more than 18 months ago, but many Gambians are still haunted by the legacy of his brutal two-decade rule.

He had refused to accept his shock defeat in elections in December 2016 and only left power at the insistence of regional leaders, who sent troops when he dug in his heels.

Last week, his successor, Adama Barrow, launched the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC), saying it was “a historic step towards discovering the truth for national healing”.

He explained that it would “investigate and establish an impartial historical record” of the human rights abuses committed from July 1994 to January 2017, which covers the period Mr Jammeh ruled The Gambia after staging a coup.

And as one of the survivors of the violence meted out during this time I want to take the stand before the 11 TRRC commissioners.

I want to expose for the record the brutality and fear that journalists have suffered.

My experience at the hands of Mr Jammeh’s torturers came without warning on 29 May 2006, when a police officer arrested me in Serekunda, about 13 km (8 miles) south-west of the capital, Banjul.

I was given no explanation for my arrest and was transferred to the central police station in Banjul.

‘A police officer’s moment of kindness’

It was already late in the evening, so a junior officer left in charge said to me that I could sleep in the office for the night.

“You should thank your stars, because all the people arrested in connection with Freedom Newspaper are usually taken to the cell below,” he said.

I sat up straight and looked into his eyes because that was the first clue I had about the reason for my detention.

I immediately asked if I could make a call from his phone, since mine had been confiscated. He hesitated but agreed – and as I found out later this kindness may ultimately have saved my life.

All night I tried to work out what had connected me to the Freedom Newspaper – as I had never filed for it or communicated with its US-based publishers. I mainly covered sport on national TV and filed dispatches for the Focus on Africa programme on the BBC World Service.

But I grew afraid, as I knew the government did not like the Freedom’s coverage – the online news site would often carry state secrets and stories about alleged human right violations in The Gambia.

The next morning, using my own car, I was taken to the headquarters of the feared and now disbanded National Intelligence Agency (NIA), where for a whole day I was made to wait – with no word from any official about why I was there.

As darkness fell, I was led to a reception hall furnished with sofas. I chose one and as I lay down, I heard voices from behind me from other sofas.

“Lamin. Do you recognise me?” one called and then another.

It was hard to see, but I could make out the face of Malick Mboob, a former colleague at The Daily Observer, who left to work as a spokesman at the Royal Victoria Hospital.

Then I recognised Lamin Fatty, a reporter for the Independent newspaper, who had also disappeared more than two months before my arrest.

I told them that everyone had been looking for them.

Both of them jokingly told me: “Cham, welcome to the club.”

‘Blows were raining down on my head’

We tried to get some sleep, but I was woken at about 02:30 and led out barefoot past the buildings to a sand pit that was ringed by heavy stone boulders.

I was asked to step into the ring and immediately eight men appeared, apparently drunk – metres away I could already smell alcohol on their breath.

Two of them I recognised to be members of the presidential guard: Tumbul Tamba, who was wearing a track suit, and Musa Jammeh, who was nicknamed “Malyamungu” after a notorious killer in Idi Amin’s regime in 1970s Uganda.

The next thing I knew blows were raining down on my head and back; boots were stamping on my feet and my hands were strapped together.

Tamba shouted: “What are you telling Pa Nderry and Omar Bah?” – Nderry was the editor of the Freedom Newspaper and Bah was suspected to be his Banjul reporter who was wanted by the authorities.

“Why do you tell lies to the BBC?” he continued.

“How much do they pay you? Don’t you know they are liars?

“Why can’t you report without mentioning President Yahya Jammeh?”

Like a conductor, Tamba would raise his hand up to signal the torturers to stop while I tried to regain my breath.

I kept telling him I did not understand his accusations, and he replied by shouting insults about all Gambian journalists.

After more than half an hour, the beating stopped and I was left with whizzing sounds in my ears.

I was then escorted to an office, followed by an officer using a cloth to wipe away my bloody footsteps. Tamba and Malyamungu also accompanied me.

In the room we were joined by two more senior National Intelligence Agency (NIA) operatives who questioned me and threatened me further – though I could not give them the answers they sought.

Later, I was taken back to the reception room. Two days later, the same pattern of torture was repeated.

I was released on the fifth day and told by Tamba that I would be monitored and my fate would be worse if I was invited again to the NIA.

I feared that my work would put me and my family in further danger – so I fled the country. With the help of friends I was able to do a course in London to take a break and later flew to Dakar in neighbouring Senegal to continue living in exile.

‘Prevent tyranny’

It was a traumatising experience – and I am still living with the effects. To this day I cannot drive near the area of the former NIA headquarters.

But I believe I was saved from further torture by the phone call I made on the day of my arrest.

I had managed to get hold of the BBC, who then contacted the British High Commission in The Gambia. Their inquiries into my whereabouts helped internationalise my case, putting pressure on the government to release me.

The two colleagues I had met in detention remained in custody for many more months.

My two main torturers, Tamba and Malyamungu, are now dead, but with my testimony to the TRRC I want to name their accomplices as I believe that when the truth is established and perpetrators exposed and prosecuted, the lesson will serve to prevent further tyranny.

As President Barrow put it: “Never again shall a few people oppress us as a nation. Never Again!”

Source: BBC

Comments are closed.