Three faded photographs of Ami as a toddler are Elhadj Diop’s only tangible mementoes of his daughter. Yet she comes alive in the intensity of his voice, as he recounts her last two days of life.

Ami was 12 when she died from malaria on 10 October 1999.

Since then Mr Diop, now 64, has channelled his grief into a unremitting campaign to banish malaria in his town of Thienaba Seck, about 150km (95 miles) from Senegal’s capital, Dakar.

He has given up his job, sold his belongings, walked hundreds of kilometres and convinced thousands of people – from politicians to village sanitation brigades – to play their part.

He is one of the reasons why Senegal is on track, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), to be declared malaria-free by 2030.

“At the time we had no idea what it was,” says the former photographer, sitting in his yard under a tree. “She was vomiting. Her limbs ached. We took her to the clinic and to the traditional practitioner.

“But only the wet cloths we wrapped around her burning body seemed to offer her relief.

“On the second day, she seemed to have improved. She asked me to buy her some apples. I was holding the bag of apples when my sister phoned with the news.”

Thursday is sanitation day

The same day as Ami’s funeral, several other children were buried in Thienaba Seck, a town of 4,000 people.

“They had died of the same illness. The day after, it was a young woman who had just had a baby. Ten days later, I lost my nephew to malaria.”

He quit his job.

“Taking photographs for Unicef, I had learnt that fighting malaria requires community involvement. I convened information meetings at my house with elders from the area.

“But of course I had to pay for their transport and give them a meal. So I sold my camera, my television set and all the electric fans in my house.”

Mr Diop goes round communities in his district, informing people about the importance of hanging a mosquito net over every bed, and the need for rigorous cleaning – in Thienaba Seck, every Thursday is sanitation day – to remove rubbish and stagnant water that attract the mosquitoes which spread malaria.

“In 2014, I walked 412km. I made myself ill. That is when one of the donors gave me a car. It was very nice of them,” he says, pointing at a battered white pick-up in his yard, ”but I can only occasionally afford to put fuel in it.”

Neighbourhood watch for cleanliness

Mr Diop is not particularly interested in receiving aid money.

“If it is offered I take it. But the donors have their own priorities. One day USAid and the Global Fund will leave Senegal and go elsewhere. If we depend on them, then what will we do?” he says.

He has convinced the households in Tienaba Seck to contribute a small amount each week to a sanitation fund. He has set up a neighbourhood watch system, whereby people check on each other’s cleanliness and report transgressors to a committee.

.

Mr Diop has strategic allies, including Alou Niasse, the district nurse who took up his post in Thienaba Seck 20 years ago.

“In those days we worked long hours – sometimes from 8am to 11pm,” says the nurse.

“Out of 100 people who walked into the health centre in the rainy season, 65 had malaria or were assumed to have it.

“We had patients on drips all over the place, even in the yard,” says Mr Niasse, aged 56.

“People had no idea what malaria was or how to protect themselves. A lot of people died. Ami Diop was one of the most striking of them.”

Mr Niasse goes through his ledger: there have been no confirmed cases this year.

“We get a few in the rainy season but they are mainly imported, by truck drivers who come from Dakar or from neighbouring countries, like Mali or Guinea.”

Malaria-free generation?

He says there has been progress on many fronts: ”We have the instant tests now, so diagnosis has improved.

“The government has introduced free treatment for under-fives. The medication has improved. But the biggest change is the community’s level of understanding and its commitment to sanitation.”

This week, Mr Diop will make a speech about his experience before 3,000 eminent scientists, including two Nobel Prize winners, who are gathered in Dakar for the 7th Multilateral Initiative on Malaria conference.

Among them will be Doudou Sene, the coordinator of Senegal’s national programme to fight malaria – a government-funded body whose work far away from the Thienaba Seck community has helped the country make great strides towards eliminating the mosquito-borne parasite.

“Senegal is at the forefront of genome research to develop ultra-sensitive instant diagnostic tests to detect even small traces of the parasite.

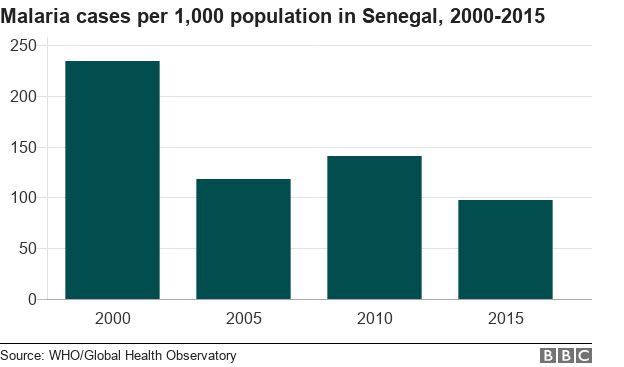

“As a country, through public information, we have reduced mortality from malaria by 40% in the past 10 years, and morbidity [the number of cases of people falling ill] by 77%.”

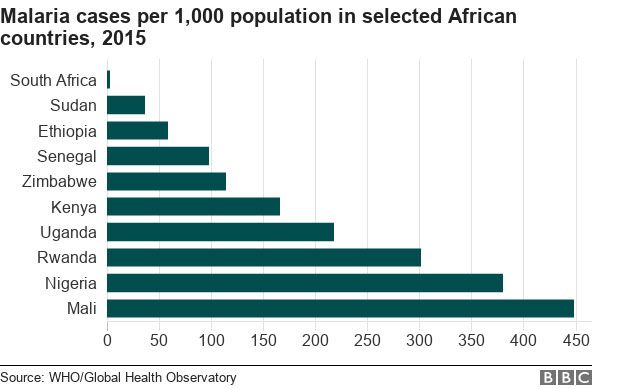

But Senegal still has challenges ahead if it is to succeed – along with Algeria, Comoros, Madagascar, The Gambia and Zimbabwe – in meeting the 2030 deadline for eliminating malaria set by the WHO.

Mr Sene says, “The hardest places are along our borders with Guinea and Mali – two countries that have made fewer strides. We still have high rates to beat in five out of Senegal’s 14 regions.”

Back in Thienaba Seck, Elhadj Diop sits in his yard and lifts up his latest grandchild. She looks just like Ami.

Thanks to his tireless efforts, six-month-old Rokaya has a real chance of taking all the love he gives her into adulthood, as a member, perhaps, of Senegal’s first malaria-free generation.

Source: BBC

Comments are closed.