After the bullet burst through his mouth and neck, Cesar Kimbirima lay in the long grass, thought of his family, and waited to die.

He had been shot before, of course. Three times in fact – leg, leg, and arm. But this was the worst.

And so, as the sky started spinning, and his consciousness faded to black, he thought it was over. His life would end in the long grass, while his blood poured into the dry Angolan earth.

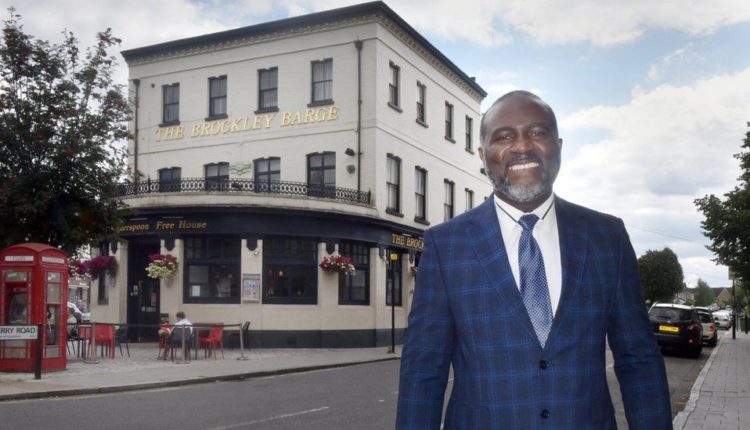

More than 20 years later, that dying soldier pours pints at the pub he manages in south London. As he chats to punters, and waves to babies in prams, there is no hint of Cesar Kimbirima’s former life.

No hint, that is, unless you look closely at his neck. Because there, just above his collar, is the scar: a reminder of the bullet, the coma, and the escape.

Cesar Kimbirima was born in Angola in south-west Africa, and grew up one of 11 siblings. His mother was a primary school teacher; his father was a nurse and electrician.

His family lived in Huambo, the third biggest city, and elsewhere in the country. And, despite the long-running civil war, he enjoyed school and was a happy child. But in 1990, when Cesar was 17, his childhood ended.

“The army got me in the street,” he says. “That’s the way it used to be. If you were big, tall, they just grabbed you and made you join. Without your father’s consent, without anything.”

He was not allowed to pack a bag. He was not allowed to say goodbye to his family – whom he then didn’t see for three years. But none of it was a surprise.

“As a kid back then, we always used to say ‘If they get me, that’s it’. Because we knew it was going on. So when you get caught, you have no choice.”

Could he run? “If you try, you might get killed. So you’d better stay there, sit down on the floor, and wait for the truck.”

The Angolan army did not – or could not – care for its soldiers. During six months’ training, the conscripts would get one meal a day. After training, when they were sent on missions, they might get two packets of biscuits, one can of condensed milk, and a water container.

Those rations were supposed to last 30 days.

“We learned how to survive,” Cesar remembers. “If you get a plastic bag, wrap it round the leaves, and seal the end, the tree will sweat. And when it starts dripping, that’s water.”

He was shot for the first time aged 18. “In the leg,” he says. “We used to camp [to protect villages in the civil war]. Left-wing forces came down and attacked us. We were kids, we had no experience.”

Cesar was shot twice more, in separate incidents, before the attack that nearly killed him.

“Normally they [the opposition forces] came in the middle of the night,” he says. “This time, they came around 8pm. We heard a noise. One of my colleagues started to run, so they started shooting. So we shot back. And then I felt really cold.”

Although he didn’t realise at first, he had been shot through the mouth. He ditched his gun – knowing he would be killed if the enemy found him with it – and kept running. After 15 or 20 metres, he lay down in the grass and felt the blood pour down his back.

“I thought about my family – that I didn’t get to say goodbye,” he says. “I thought, that’s it – my life has ended. That’s it – another young guy is gone. That was my thinking. That’s the last thing I remember.”

Cesar woke up in a hospital – “I didn’t believe I was alive” – and was treated for two or three days. But then he went into a coma, where he stayed for five months. When he woke up, the doctor told him he wouldn’t walk again.

There was some good news. After nine years in the army, he was discharged – they did not want a soldier who could not walk. But there was bad news, too. He was 26, with no money, and no idea how to find his family – which by now included the mother of his child and their three-year-old daughter. He left hospital with nothing but a pair of wooden crutches.

“It was a survival situation,” he says. “I was begging for food and money, and somewhere to stay.”

Source: BBC

Comments are closed.