As Christie’s in London collaborates with Efie Gallery to present an exhibition of West African art entitled Material Earth, we talk to the gallery’s co-founder, Kwame Mintah, about why Ghanaian artists in particular are attracting so much attention worldwide

In recent years, much has been made of Ghana’s thriving contemporary art scene. Artists such as El Anatsui, Ibrahim Mahama, Amoako Boafo and others have been making a considerable name for themselves internationally.

In El Anatsui’s case, this has involved exhibitions such as Gravity and Grace, which toured major US institutions in 2013-14. Boafo’s works, meanwhile, have achieved stunning sale results: in December 2021, his painting Hands Up fetched HK$26.7 million ($3.4 million) at Christie’s in Hong Kong, matching the record auction price for a work by a West African artist.

In 2019, Ghana hosted its first-ever pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Numerous galleries with an emphasis on Ghanaian art have also appeared, both inside and outside the country. One of these is Efie Gallery, which earlier this year opened its doors in Dubai.

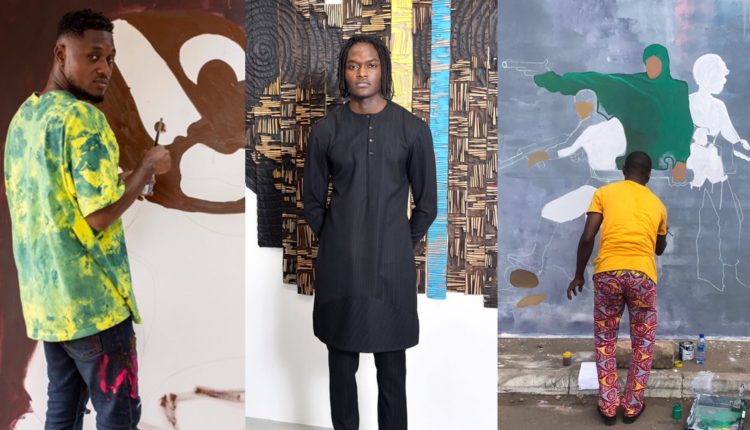

From 28 April until 13 May, it is collaborating with Christie’s in London to present the exhibition Material Earth. This will feature work by El Anatsui alongside that of two younger, but similarly pioneering, Ghanaian artists: Isshaq Ismail and Yaw Owusu.

Below we speak to Efie Gallery’s co-founder, Kwame Mintah, about Material Earth and why Accra is 2022’s artistic hotbed.

Other than their nationality, what do the three artists in Material Earth have in common?

Kwame Mintah: The exhibition aims to contribute to the current global debate about sustainability, materiality and waste. El Anatsui and Yaw Owusu do that quite obviously, with sculptural works that involve the repurposing and upcycling of found objects. [The former is renowned for his shimmering tapestries made with bottle tops, the latter for rich abstractions created using coins.]

Isshaq Ismail fits in slightly differently. He creates wildly expressive portraits that explore notions of the grotesque. These figures could never be called realistic, and their lack of humanity is really a reflection of our own lack of humanity.

In the 21st century, there is a sense that mankind, which traditionally was considered part of the natural world, is now becoming material — literally. Ecologists at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam in the Netherlands recently discovered that traces of microplastics can be detected in human blood.

Is Ghana a hotbed of contemporary art?

KM: Very much so. The list of artists from the country now seeing the fruits of their labours is remarkable. As a Ghanaian myself, however, I feel I should slightly counter this by noting that art has been made in Africa since time began. It’s just that now it is being seriously seen, appreciated and purchased abroad.

Why do you think that is? Why the sudden attention?

KM: An amalgamation of reasons, really. One of these is increasing racial awareness and a greater appreciation of African culture in the West. There have also been a lot of diaspora Africans, who have done well in their different professions internationally, now getting back in touch with their roots. One way they’re doing that is through art. Around half of our collectors at Efie Gallery are of African descent.

I think it helps, too, that the work being made is so fresh. Artists of all ages are producing innovative pieces — from established figures such as Larry Otoo to hot young talents such as Kwesi Botchway.

Might we also mention artists returning to their roots, when we talk about diaspora?

KM: Yes, certainly. Ghana’s pavilion at 2019’s Venice Biennale was a good example. Two of the six participants, John Akomfrah and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, were British Ghanaians. And the pavilion itself was designed by Sir David Adjaye, a British Ghanaian architect.

Is the art scene centred mainly on Accra, or is it spread throughout the country?

KM: Accra is Ghana’s capital city, and it’s generally where people convene and most of the action is. It’s where the Chale Wote Street Art Festival takes place, for example, and where the Nubuke Foundation [a non-profit institution in support of emerging artists] is located.

Accra is also home to the majority of galleries — perhaps most notably Gallery 1957, which opened in 2016. This has really been a game-changer for art in Ghana. It now has a total of three spaces across the city, but the original was the key one, strategically located within the Kempinski Hotel Gold Coast City Accra. This is a five-star hotel where government officials, businessmen and other important individuals stay — and having a gallery there, showing work by contemporary West Africans, gave the art scene a massive boost.

It should be said, though, that there are many artists working outside Accra, too. [Ibrahim Mahama, for example, another of the participants in the 2019 Venice Biennale pavilion, has set up three art spaces in his home city of Tamale, in northern Ghana.]

Comments are closed.